Terrorism Suspect Policies and the USA PATRIOT Act

Testimony discusses the importance of the right to counsel and Fifth Amendment protections.

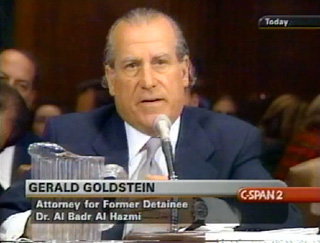

Gerald H. Goldstein testified on May 25, 2010 with regard to the detainment of Dr. Al-Badr Al Hazmi, Terrorism Suspect Policies and the USA PATRIOT Act. The article discusses the importance of the right to counsel and why Fifth Amendment protections must apply to citizens and non-citizens alike.

The testimony also addressed the new rule announced on October 31, 2001 in a notice from the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The new rule announced in the Federal Register gave the Federal government authority to monitor communications between people in Federal custody and their lawyers if the Attorney General deems it “reasonably necessary in order to deter future acts of violence of terrorism.”

Table of Contents

Gerald Goldstein Testimony on Terrorism Suspect Policies

Mr. Chairman and Distinguished Members of the Committee:

In the early morning hours of September 12, 2001, Dr. Al-Badr Al Hazmi, a fifth-year radiology resident at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, Texas, was studying for his upcoming medical board exams, when federal law enforcement agents entered his home, searched the premises for some six hours, and took Dr. Al Hazmi into custody. Immigration authorities transported Dr. Al Hazmi to the nearby Comal County Jail.

Later that afternoon, Dr. Al Hazmi was allowed a brief telephone call to my office, at which time he explained that he was being held by United States Immigration authorities and inquired as to the reasons for his detention. Almost immediately, an Immigration and Naturalization Agent took the telephone and told me that he could provide no information regarding the reason for my client’s detention, nor his whereabouts; he then referred me to his “supervisor.”

After my numerous telephone calls to the supervising agent on September 12th and 13th went unanswered, I wrote a letter to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, seeking to ascertain the whereabouts of my client and requesting an opportunity to communicate with him. In no uncertain terms, my letter explained:

I am concerned with regard to the status of [Dr.] Al Hazmi and am requesting that information regarding his status and provisions for my office to communicate with him be provided at your earliest convenience. . . . In light of your unavailability and my expressed concern regarding the need to communicate with [my client], I am copying this letter to the United States Attorney’s Office in the hopes that they may help facilitate same. (See attached letter to INS Agent, dated September 13, 2001).

Dr. Al Hazmi’s repeated requests to consult with his attorney were ignored, as authorities continued to interrogate him. As he would later tell a reporter, “Nobody explained to me anything, they just kept saying, ‘Later, later,’. . . I said, ‘I need to call my lawyer.’ They said, ‘Later.’ ‘I need to call my wife.’ They said, ‘Later.’” Macarena Hernandez, Prayers Answered, Dr. Al-Hazmi Details How Faith Aided Him During His Detention, San Antonio Express-News, Sept. 30, 2001, at 1A.

On September 13, 2001, my office retained an immigration attorney, and both counsel filed formal “Notice[s] of Entry of Appearance as Attorney” on INS Form G-28. (See attached Forms G-28, Notices of Appearance as Attorneys for attorneys Gerald H. Goldstein and Robert A. Shivers).

When I was finally able to reach the “supervising” INS agent, on September 14, 2001, he advised that he too was unable to provide me with access to, or any information regarding my client, referring me instead to an attorney with the Immigration Services’ Trial Litigation Unit. However, when I reached the Immigration Services’ attorney, he advised that he could not speak to me about Dr. Al Hazmi and would not provide any information regarding the whereabouts of my client.

On that same day, Mr. Shivers, the immigration attorney hired by our firm, sent a letter to the District Director of the Immigration Service, detailing counsels’ repeated attempts to determine the whereabouts of our client, again requesting an opportunity to consult with Dr. Al Hazmi, and expressing his concern that “misrepresentations were knowingly made to prevent our consulting with our client.” (See attached letter to INS District Director, dated September 14, 2001).

I then sent a letter to the acting United States Attorney for our district (copying the Assistant United States Attorney whom I had been advised was assigned the case), again attempting to ascertain the whereabouts of my client and making a “formal demand” for an opportunity to consult with him, thus:

What is of particular concern to me is that despite prior notice to your office . . . of my client’s desire to communicate with counsel and my attempts to locate and speak with him, my numerous calls to your offices have gone unanswered. A . . . trial counsel for INS did call me back only to advise that he could not talk to me or even advise me where my client was being detained. . . . After both Mr. Shivers and I filed our respective representation forms, and after Mr. Shivers spent the better part of the day attempting to locate and visit our client, [the] INS District Director . . . advised that our client had been placed on an airplane and removed from this ‘jurisdiction.’ Even an individual being deported . . . is entitled to be represented by counsel, and a reasonable opportunity to consult with their counsel.

Accordingly, I am hereby making another formal request for same.

(See attached letter to U.S. Attorney, dated September 14, 2001).

Earlier that day, Dr. Al Hazmi had been taken by FBI agents to New York, and held in a lower Manhattan detention facility, without an opportunity to contact his family as to his whereabouts or have any contact or consult with his attorney.

The following sequence of events brought this Kafkaesque experience to a conclusion:

- On September 17, 2001, almost a week after my client had been taken into custody, I was advised that he was being detained by Federal authorities in New York City

- On September 18, 2001, local New York counsel, hired by my office, was advised by the detention facility authorities that he would not be permitted to visit with Dr. Al Hazmi, because the court had appointed a different lawyer to represent him, without Dr. Al Hazmi’s knowledge.

- On September 19, 2001, the local counsel hired by my office was permitted to visit with Dr. Al Hazmi at the Manhattan detention facility.

- On September 24, 2001, the FBI cleared and released Dr. Al Hazmi. He returned home to San Antonio the following day.

The Department of Justice has denied that any of the detainees are being held incommunicado, suggesting that any interference with the right to counsel was due to time compression and administrative shortcomings. However, as the above scenario demonstrates, Dr. Al Hazmi was not someone who simply “slipped through the cracks.” Dr. Al Hazmi was represented by retained counsel who had filed formal notices of appearance on behalf of their client.

Moreover, Dr. Al Hazmi’s attorneys had notified the appropriate law enforcement agencies and the Department of Justice in writing, requesting the whereabouts of their client and expressing their desire to communicate with him. Despite these efforts — and despite Dr. Al Hazmi’s repeated requests to consult with his counsel — Federal authorities stonewalled and continued to interrogate Dr. Al Hazmi in the absence of his counsel.

By denying Dr. Al Hazmi access to his retained counsel, Federal law enforcement officials not only violated my clients rights, they deprived themselves of valuable information and documentation that would have eliminated many of their concerns. Their obstructionism prolonged the investigative process, wasting valuable time and precious resources.

Dr. Al Hazmi’s experience, when viewed in conjunction with the Department of Justice’s and various law enforcement agencies’ policies that interfere with attorney-client relations, suggests that this Committee’s continued vigilance is warranted.

Other Examples – Israelis Jews in Federal Detention for a Month

For example, eleven Israeli citizens were presumably mistaken for Arabs and arrested in Ohio for working without authorization while visiting the United States on tourist visas. They were visiting this country after completing military service in Israel, where several had served in counter-terrorism units.

In hours-long interrogation by the FBI, the Israelis were told that getting counsel involved would only complicate things and prolong their detention. Nine of the eleven were detained for more than two weeks and two were detained for a month. All have now been granted voluntary departure. See John Mintz, 60 Israelis on Tourist Visas Detained Since Sept. 11, Washington Post, Nov. 23, 2001, at A22; Tamar Lewin & Alison Leigh Cowan, Dozens of Israeli Jews Are Being Kept in Federal Detention, New York Times, Nov. 21, 2001; NACDL interview with David Leopold, Esq., Cleveland, Ohio, counsel for the detainees.

According to counsel for the detainees, during the course of the questioning at least one of the Israelis was asked “how much torture can you stand before you tell the truth.” The FBI also repeatedly asked the Israelis who sent them to the United States, whether they took any pictures of tall buildings and whether they had any Israeli intelligence connections or role.

Each was also asked whether he or she was Muslim and whether they had visited a mosque in Toledo, Ohio. On the night of their arrests, the two women in the group were subjected to a humiliating “pat down” by a male INS officer as a prerequisite to their use of the restroom. The male INS officer claimed there were no longer any female officers present at INS Headquarters.

The Importance of the Right to Counsel

The right to the assistance of counsel is the cornerstone of our adversarial system. One need only read Miranda v. Arizona, which recounts the widespread abuses that plagued our nation’s interrogation rooms, to fully appreciate the risks that accompany any abrogation of the right to counsel. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 445-446 & n.7 (1966) (providing examples of abuses and explaining that “[t]he difficulty in depicting what transpires at such interrogations stems from the fact that in this country they have largely taken place incommunicado.”).

These are among the concerns that mandate a right to representation not only when one is charged with a crime, but when one is subjected to custodial interrogation as well. It is well-established that once an individual in custody requests counsel, all further questioning must cease. Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477 (1981); Minnick v. Mississippi, 498 U.S. 146 (1990).

The government’s current dragnet-style investigation — characterized by ethnic profiling, selective enforcement of criminal and immigration laws, and pretrial detention for petty offenses— heightens the important role counsel plays from the very inception of custody.

A separate issue, and one that will be discussed more fully by other groups, is the extent to which these ethnically biased law enforcement tactics violate the Constitution and international laws, and tarnish our country’s image. Singling out non-citizens for disparate treatment raises serious constitutional questions. See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

Fifth Amendment Protections Must Apply to Everyone

As the Supreme Court recently reaffirmed, the Fifth Amendment protects all non-citizens, even those here unlawfully, from deprivation of life, liberty or property without due process of law. Zadvydas v. Davis, 121 S. Ct. 2491, 2500-2501 (2001). Policies which evade these protections not only erode minority and immigrant confidence in law enforcement, but undermine efforts to obtain adequate rights and protections for United States citizens traveling abroad.

The interests protected by defense counsel go beyond the procedural protections guaranteed by the Bill of Rights. As recognized by the Innocence Protection Act, introduced by Chairman Leahy and supported by NACDL, without the effective representation of counsel, not only are innocent persons incarcerated or worse, but the guilty go free.

The Right to Counsel is an Important Check on Government Power

The right to counsel also serves as an invaluable check on the illegitimate or indiscriminate use of government power. At no time is this right more important than when the government has acquired or claimed sweeping new powers. As Justice Brandeis said in his famous dissent,

“Experience should teach us to be most on our guard to protect liberty when the government’s purposes are beneficent…. The greatest dangers to liberty lurk in insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning but without understanding.” Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 479 (1928) (Brandeis, J., dissenting).

The USA Patriot Act

The USA PATRIOT Act gave broad new powers to federal law enforcement in the areas of eavesdropping and electronic surveillance, search and seizure, money laundering, criminal and civil asset forfeiture, information sharing (e.g., erosion of wiretap and grand jury secrecy rules), and detention of non-citizens.

To determine whether these powers are being exercised in a responsible manner or whether they are being abused, and therefore need to be curtailed, public disclosure and oversight is essential. This accountability is enhanced by defense lawyers, many of whom have already brought their cases of abuse to public light.

While my client has been completely absolved of any wrongdoing or connection to the acts of terrorism, I am still prohibited by court order from discussing certain aspects of the case. The extraordinary secrecy which has characterized the post-9/11 investigation has made it difficult for defense lawyers to discuss the facts surrounding their clients’ detentions and impossible for the public to gain a complete picture of the government’s tactics. Many of my colleagues who represent past or current detainees share my view that this veil of secrecy serves only to shield the government from criticism.

Federal Government Monitoring Attorney / Client Communications

Before concluding, I would like to discuss one more issue, which is closely related to the denial of access to counsel. On October 31, the Federal Bureau of Prisons published notice in the Federal Register of a new rule giving the Federal government authority to monitor communications between people in Federal custody and their lawyers if the Attorney General deems it “reasonably necessary in order to deter future acts of violence of terrorism.”

Instead of obtaining a court order, the Attorney General need only certify that “reasonable suspicion exists to believe that an inmate may use communications with attorneys or their agents to facilitate acts of terrorism.” Until now, communications between inmates and their attorneys have been exempt from the usual monitoring of other calls and visits at the 100 federal prisons around the country.

NACDL joins the American Bar Association and the vast majority of the legal profession in denouncing this new policy. The attorney-client privilege — “the oldest of the privileges for confidential communications known to the common law” — is the most sacred of all the legally recognized privileges.

Its root purpose is “to encourage full and frank communications between attorneys and their clients and thereby promote broader public interests in the observance of law and administration of justice. The privilege recognizes that sound legal advice or advocacy serves public ends and that such advice or advocacy depends upon the lawyer’s being fully informed by the client.” Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383, 389 (1981).

Conclusion

Based on my 32-years experience, defending persons from all walks of life, I can tell you that the crucial bond of trust between lawyer and client is hard-won and easily worn. This is particularly true when the attorney must bridge cultural, ethnic and language differences.

Any interference from the government can permanently damage this relationship, threatening the defendant’s representation and the public’s interest in a just and fair outcome — not to mention the government’s interest in obtaining cooperation in its investigations. In all likelihood, the mere specter of monitoring will complicate the already difficult endeavor of communicating effectively with incarcerated clients and will chill the delicate relationship between the accused and his advocate.